Image: What do planets outside our solar system, or exoplanets, look like? A variety of possibilities are shown in this illustration. Scientists discovered the first exoplanets in the 1990s. As of 2022, the tally stands at just over 5,000 confirmed exoplanets. As Earthlings, we seem to have an unstoppable craving for imagining living on other planets. Why? Credits: NASA/JPL-Caltech

This article was written by Mario Veen. (Jan. 2023)

Earthucation: Using interdisciplinary philosophy, education, and science communication to understand the climate crisis

We live at a peculiar time, not just in human history, but in the history of Earth. Humans now play a large role in determining their future and part of the future of the planet. While Earth has lived through a dozen or so major environmental crises in its long history,1 humans were not around to experience them. And while Earth has a future beyond human beings, whether humans will be part of this future is an open question. Will humans exist beyond what many have called the Anthropocene?

Understanding our time on Earth is urgent. What we need to do – or rather, stop doing – is already clear. This is not a matter of philosophy or science – though perhaps they can contribute to it – but rather of politics and action. In the words of geologist Marcia Bjornerud, “There are two ways for the Anthropocene to draw to a close: either we learn to be better Earthlings, blending into the background and no longer distorting biogeochemical cycles, or we go extinct.”2 This message is clear and there is no mystery around it. We have known it for a long time. There is plenty of space and plenty of resources for human beings – all 8 billion of them – to coexist with Earth and other Earthlings.

As the climate scientist Kimberly Nicholas points out, “The basic political framework to solve the climate crisis”3 already exists. Politicians have said all the right things. Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte said it most clearly at COP26: “Action, action, action.”4 Rutte, who has led four Dutch governments since 2010, joined a group of countries that promised to end all investments in foreign fossil fuel projects by the end of 2022.5 The conference took place six years after the Paris Agreement, in which 193 states agreed to do what is necessary to limit global warming to well below 2.0 degrees, and preferably to 1.5 degrees. At the time, 1.5 degrees was considered relatively safe, but the projected climate change impacts of even 1.5 degrees are turning out to be worse than expected.6 But instead of upgrading their emission pledges to fit the latest scientific evidence, governments worldwide continue to break their promises.

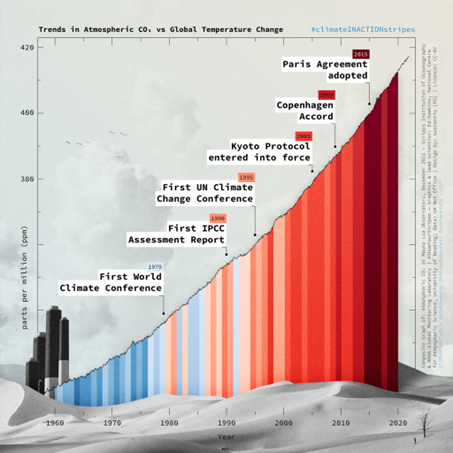

So, what do we need to understand? That the Dutch government, like many other governments, broke its promise and will continue to invest 7.5 billion Euro yearly?7,8 Politicians breaking promises is not a new phenomenon, nor is their receptiveness to the fossil fuel industry lobby. Climate inaction is no new phenomenon, as is clearly illustrated in a now well-known graph that plots the 26 climate conferences against the earth’s rising yearly average temperature. (See Figure 1)9 The people who are now over 50 years old were starting their careers when the then-nascent climate crisis, which is now a reality, could have been avoided. As the philosopher Bruno Latour wrote: “But here we are: what could have been just a passing crisis has turned into a profound alteration of our relation to the world. It seems as though we have become the people who could have acted thirty or forty years ago – and who did nothing, or far too little.”10

Rutte, born in 1967, is part of this generation, and so is the vast majority of those who are now in power. This generation has heard endless talk about sustainability, saving the environment, global warming, preventing the ice caps from melting, and so on. They have seen – or at least heard news about – the increasingly alarming messages issued by the IPCC, NASA, the World Health Organization, the United Nations, and other institutions, and have done nothing or far too little in response. Still, in 2022, even after the UN warned that “current emission pledges will lead to catastrophic climate breakdown”11 and the World Health Organization called climate change “the biggest health threat facing humanity,”12 there has been little sign of “action, action, action” or even of “action, action”.

Figure 1: Atmospheric CO2 vs. global temperature change and climate conference dates, 1958-2020, by @MuellerTadzio, @wiebkemarie, @MariusHasenheit, @sustentioEU [PG] (on Twitter); see right side of image for more authors/sources, CC BY 4.0

It’s Easier to Imagine the End of the World Than the End of Capitalism

These facts can make one cynical. But what is there to understand? The psychology of addiction is well understood. Health warnings and pictures of cancerous lungs have limited effectiveness in making people quit smoking. Factor into this the professional “merchants of doubt”, like the ones the tobacco lobby employed in the 1950s to delay government action on tobacco by casting doubt on the scientific consensus and employing effective media strategies such as “both-sideism”. Though the scientific consensus was clear at the time and still is, tobacco causes many deaths and policy has been slow to change. As documented by Oreskes and Conway,13 the merchants of doubt that worked for the tobacco lobby then started to work for the climate denialists. They have been effective for a long time in casting doubt on climate change, its anthropogenic causes, its catastrophic consequences for human existence on this planet, and our responsibility and ability to fix it. What more do we need to understand about the toxic mix of cynical politics, the influence of lobbyists, and outright science denial that we don’t already understand?14,15 But though outright climate denial has helped to muddy public awareness of the climate crisis, today it is a vocal but minor factor, just as there are people who believe the coronavirus is not real, the earth is flat, and the moon landings were faked. Rutte, and most other politicians and industry leaders and ‘boomers of power’, are not outright science deniers. Even science denial is nothing new and is largely understood.16

Still, educated people I speak with today about the ecological and climate crisis often echo the talking points invented by the merchants of doubt. The planet isn’t not warming, they say. If it’s warming, it’s not us. If there is evidence that it’s warming and it’s us, we’re not sure and we need more evidence before we can justify taking action. It may be warming, it may be us, we may be sure, but it’s not bad, because climate change has been a thing forever. But even if it’s warming, we’re sure it’s us, and it’s bad, we can’t fix it. It‘s too late now to do anything to prevent the climate crisis. And if it’s not too late, it’s unrealistic to take collective action now. What can I do, what can we do? We’re just a drop in the ocean, even if we would take climate action, it would not matter. Look at China, look at the United States. They are responsible for a large percentage of climate change, so what does it matter what we do in, for instance, The Netherlands, even though the consequences of inaction for our farmers, industry, and economy are huge? We are not responsible. It’s too big. It’s easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.17 This is the ‘climate inaction bingo’ I’ve been hearing whenever I speak with someone who does not treat the climate crisis as a crisis.18

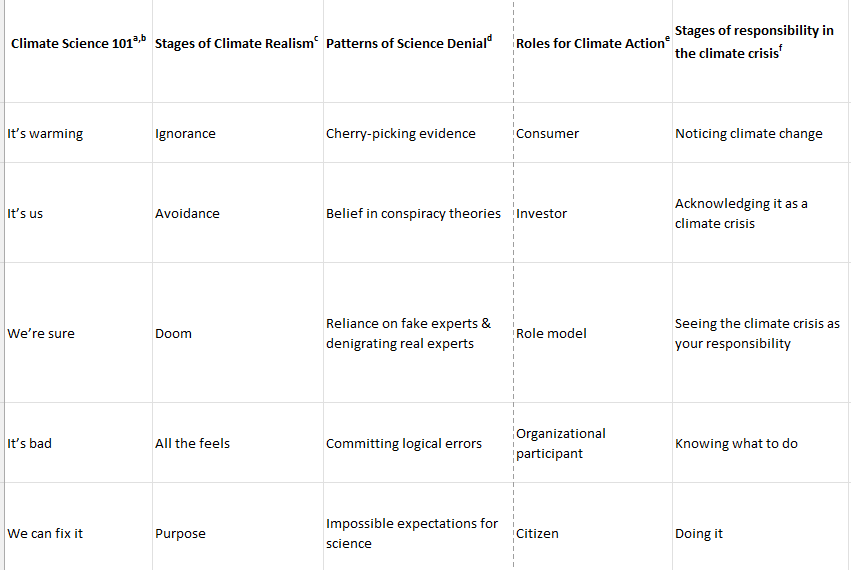

Table 1: 5×5 Climate Consciousness: integration of interdisciplinary knowledge on the climate crisis

a Nicholas, K. “Climate Science 101: Five Things Everyone Needs to Know” b Krosnick, J.A., Holbrook, A.L., Lowe, L. et al. The Origins and Consequences of democratic citizens’ Policy Agendas: A Study of Popular Concern about Global Warming. Climatic Change 77, 7–43 (2006). c Nicholas, K. (2021) Under The Sky We Make: How to Be Human in a Warming World. G.P. Putnam’s Sons. d McIntyre, L. (2021) How to talk to a Science Denier: Conversations with flat earthers, climate deniers and others who defy reason. MIT Press. e Nielsen, K.S., Nicholas, K.A., Creutzig, F. et al. The role of high-socioeconomic-status people in locking in or rapidly reducing energy-driven greenhouse gas emissions. Nat Energy 6, 1011–1016 (2021). f Frantz, C.M. and Mayer, F.S. (2009), The Emergency of Climate Change: Why Are We Failing to Take Action? Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 9: 205-222.

Knowing for the Better?

Perhaps here we are touching on a thought that needs to be understood more clearly. Most people are not science deniers. I am confident the largest portion of the voters and politicians in The Netherlands know climate change is a problem. In 2022, they experienced the warmest day on record in The Netherlands; they’ve seen a third of Pakistan flood and most of the United States freeze. Still, this isn’t enough for citizens to vote out the politicians who do not propose radical climate action, or to take to the streets by the thousands, or even speak up at every opportunity they can. This is true for most people who have the power of their vote, their voice, and their wallet. But another thing we understand well is how democracy – I’m writing from my own context of the Global North – works, the influence of populism, the way people vote, and so on. But here is something that we – at least, I – do not yet understand.

Most people no longer smoke. When they do, they don’t do it in front of children or when they’re pregnant. Most people have been vaccinated at least once. More people are becoming vegetarian as they learn about the rampant cruelty in industrial farming. Most people followed social distancing rules during the Covid-19 pandemic. Yet they do not vote out politicians whose climate actions are guaranteed to make the future of our children far, far worse than ours. Instead, we enjoy life in our relatively stable and prosperous bubble. For the majority of people, it is more comfortable to be in denial about the lessons of climate science. But from the perspective of their children and grandchildren, it is inexcusable.

But what about the people and organizations who should know better because science guides their other actions? For instance, the healthcare sector is well aware of the threat that the climate crisis poses to its core mission of maintaining public health.19,20 Globally, the healthcare industry is also a part of the problem, as it’s responsible for a significant portion of CO2 emissions, waste production, and other factors that are making a bad situation worse.21 “If the global health care sector were a country, it would be the fifth-largest greenhouse gas emitter on the planet.”22 Healthcare professionals also have the scientific literacy and resources to study climate science, and they generally trust scientific expertise.

Yet, the healthcare sector is not treating the climate crisis as a crisis – in their case, a health crisis. While ‘sustainability’ is on their agenda, and some efforts are made to limit travel, recycle, and so on, the climate crisis is not a top priority. For instance, green teams in hospitals and university medical centers are mostly unfunded and seen as a passionate group of volunteers. Recently, I was at a sustainability-themed conference with over 7,000 medical experts, educators, and scientists. While many presenters started their presentation with “I’m not an expert on climate science, but…”23, not one climate scientist was present. While the issue is clearly on the agenda, as it clearly was at this particular conference, it is troubling that no one thought of inviting an actual climate scientist. There are plenty of experts well-versed in climate, science communication, and institutional change who would be able to say exactly what the science tells us we should do and when. Remember, we already have all the science, knowledge, technology and politics to be able to take all the actions that we need to take. Instead, the healthcare sector and many other sectors who should know better are choosing not to consult the experts, not to devote a significant portion of their budgets to mitigation and adaptation of the climate crisis, and generally not acting in an evidence-based fashion when it comes to climate. In the case of healthcare and medical education, what I am struggling to understand is why the people who are using evidence-based practice in the interests of health are now in denial about the science and continue to promote evidence-based policies to worsen an impeding health crisis.

There is something to understand here, for sure. But this is not the type of understanding I am getting at. This is the type of understanding I had about smoking tobacco while I continued to be a smoker for many years. It did not make any difference. Having knowledge of the harmful effects of smoking while lighting cigarettes every day did not lead to transformative action, but rather to frustration, anger, cynicism, and shame. This is what I am feeling myself today. I am angry because I live in a country where government, organizations, and industry are breaking their promises, failing to abide by judges’ decisions, and ignoring the clearest and most important scientific message of our time. At the same time, they are killing the messenger, in the sense that people who speak out about the climate crisis are seen as extremists at worse, or well-meaning, idealistic passionate (but unfunded) people at best. This is the case with the people who speak out in meetings, but especially for climate activists. They are not just ignored – journalists and other professionals still largely see them as extremists, alarmists, and nuisances. The irony is that climate activists often carry picket signs that call for the government to keep its promises, heed a judge’s verdict, or listen to climate scientists, or even present the science in its simplest form, the ‘climate haiku’: “It’s warming. It’s us. We’re sure. It’s bad. We can fix it.”24 Perhaps the last part is most threatening for scientifically literate people. If there was no possibility to fix climate change (even now), they would be able to avoid responsibility. And with regard to fixing it – in the sense of preventing the worst consequences of the climate crisis – as Greta Thunberg writes, what we must do is crystal clear: we cannot be a little bit sustainable. Just like the thin ice you’re walking on, it either holds your weight or it doesn’t.25

Climate psychology goes a long way to help us understand why educated people fail to act to save themselves and their children. There is the bystander dilemma, the diffusion of responsibility problem, cognitive dissonance, and so on. For instance, if the generation that might have prevented the climate crisis acknowledges climate science, they must also implicitly acknowledge their responsibility for creating the problem we now face and for continuing to make it worse. Just as my frustration about smoking only made it harder for me to quit.

Climate Psychology

But when I smoked, I harmed only myself. I’m not sure how much consolation these understandings will be to the children and grandchildren of the complacent when they wonder why their parents and grandparents didn’t do what was necessary. The more important job of climate psychology instead might be to offer therapy and consolation to those who are advocating for science-based action on climate and are getting burnt out, frustrated, and desperate because of the inaction (or outright hostility) of ‘the adults in the room’. It is crucial that climate activists, who are the science advocates of our time (many are scientists themselves), continue to muster the energy to keep telling the truth and holding the rest of us accountable. Holding us accountable must entail civil disobedience, in which activists literally put their bodies and reputations on the line in the hope that someone might listen. As long as their actions do not harm any people or animals, it’s hard for me to imagine an action that is not justified if it is effective in instigating policy change with regard to climate.

In fact, I am wondering why more people are not blocking freeways or doing whatever else they can for the sake of their children’s futures. In a word, climate activism and civil disobedience are – at least for now – the most evidence-based actions an average citizen can take. Some of us can do more, though at less risk to our physical, financial and legal well-being.24 We can speak up at meetings, instigate organizational change, and call attention to climate science. Ironically, being effective in this latter category often means softening the science, using euphemisms, and feigning enthusiasm over actions that are well-meant but do little for the climate. Perhaps climate psychology can help here too, in teaching us how to deliver the bad news of climate science without triggering denial, hostility, being ignored or even losing one’s job. And although most people are in denial about the findings of climate science rather than science-deniers, books like How To Talk To A Science Denier offer practical tips.16

Though climate psychology and climate science are crucial, they have been pretty well understood for some time now. Instead, I focus on an understanding of three entangled fields: interdisciplinary philosophy, interdisciplinary education, and interdisciplinary science communication. The philosopher Isaiah Berlin made a distinction between philosophical questions and scientific questions by saying that in science, the question may be unresolved but the method for getting the answer is clear.26

In this sense, the climate crisis is an interdisciplinary scientific problem. It cannot be repeated often enough: from a scientific, technological perspective, it’s clear what we need to do and that we can do it. Interdisciplinary science communication means we need to learn how to communicate this from the perspectives of geology, physics, engineering, political science, sociology, psychology, biology, communication, and disciplines in the humanities such as those that study social justice. I call this science communication rather than science, because all the knowledge is already there. The problem is that these science and academic disciplines do not talk to each other, or far too little. When they do, they often do not understand each other.

Interdisciplinary science communication has a triple meaning. First, mediation and stimulating communication between scientific disciplines (physics, psychology, politics) and departments (Science, Social Science, The Humanities, Logic). Second, stimulating and facilitating communication between scientific and academic experts in different disciplines and different departments (natural scientists and humanities academics, for instance, or transition scholars and medical experts) and different regions (e.g., political scientists from the United States and The Netherlands), and different levels of applied-ness, from theoretical physicists to action researchers, political organizers, and so on. Interdisciplinary science communication also means recognizing which voice represents the expertise in which contexts. For instance, climate activists, community nurses, and victims of climate-induced catastrophes might have knowledge of what actually works in the real world that those in academic circles lack.

In addition to communication between scientific disciplines and departments, and between scientific communities and other experts, the third component of interdisciplinary science communication is that of communicating with and to the public. This is fairly simple: whenever you have people’s listening, communicate Climate Science 101 and use it as a basis for a conversation (See Table 1 for my ‘cheat sheet’). Good science communication is a dialogue that informs others about the state of the art of science but also leaves room for the other’s feelings and thoughts without invalidating them. It also builds or takes place in relationships. This can be a professional relationship – for instance, in The Netherlands, the General Practitioner (family doctor) is among the top five most-trusted sources of climate information.27 But if you have the resources to educate yourself, your family, friends and colleagues will be more likely to trust your science communication than that of a stranger or the media. And this is not an either/or choice if your voice amplifies messages that are getting via by scientific sources, the media, and activists.

Education: Learning by Doing

Although science communication is a field in itself, interdisciplinary science communication in the sense I have described is in urgent need of being understood. Here, understanding means studying (studying the literature, doing experiments and research projects) but also learning by doing: what works, for whom, and under what circumstances? One pitfall to avoid is taking the easy way out by communicating a positivistic, solutionist, and scientistic model of science. The unrealistic expectations of science are grist for the mill of science deniers,16 and such a model is detrimental to the crucial role of the social sciences and the humanities in understanding the climate crisis.

The second component is education, of which science communication is an important part. But it is not the whole story. There are many ways to look at education, but my main framework for understanding it is as a way to move from reality to actuality.28 Reality is the world you experience, while actuality is the world as it actually is. While there is much to be said about this, the bottom line is that collectively (globally) we live in a reality in which the climate crisis does not exist.

Again, we can draw a historical comparison with tobacco. There was a time when doctors were featured in tobacco company advertisements and recommended certain brands of cigarettes as good for the throat.29,30 In reality, they said, smoking was harmless, enjoyable, and perhaps even good for you. In actuality, many smokers developed cancer. The psychological mechanisms I referred to earlier are examples of our in-built tendencies to live within the stories others tell us and we tell ourselves, rather than to face the existential situation we find ourselves in. Education is a way to lead someone out of a reality into, perhaps not actuality, but at least a more truthful reality. Education often takes place in institutions, but it doesn’t have to. Take hygiene as an example, particularly during the Covid pandemic. All of us had to educate ourselves on what to do to avoid a literal collapse of society. This came down to simple actions such as social distancing, working from home, and washing one’s hands. But the basis of this was education and, as part of this, science communication.

Education starts with educating oneself. What do I already understand, what do I not yet understand, and how can I study it? Educating oneself can involve taking a course or even completing a university education, but it can be as simple as listening to a podcast, reading a book, or talking to experts. Many climate scientists are excellent educators, and there are plenty of accessible and reliable educational resources online. And next time you walk past a climate demonstration, you could speak to the activists. Ask them who they are, what their background is, why they are there, and what they’re hoping to achieve. Conversation is the easiest and most effective form of education. So, speak with everyone around you about the climate. Even if they don’t know more than you, you can find out many things in an honest conversation.

What we need to understand urgently with regard to education is how to make it truly interdisciplinary, how to build on interdisciplinary science communication, and which educational strategies work. This requires interdisciplinary educational research, but also practice. For instance, the ‘bad news conversation’ I referred to earlier is a well-studied practice in delivering bad news to patients while educating them about their situation and what they can do or what they need to accept.31 Here, too, we can build on the expertise that climate scientists have built painstakingly and out of necessity. Kimberly Nicholas, for instance, calls for paying attention not just to the facts but also to what she calls “all the feels” in education.3 She has also designed Climate 101 workshops.32

But education can also take place on an interpersonal level. The greatest challenge in education with regard to the climate crisis may be that we typically regard education as a primarily rational matter. But educational forms that acknowledge and build on the emotions the existential reality of the climate crisis evokes may be more effective. For instance, teach Climate 101, and as a take-home assignment ask participants to take the age of their child, grandchild, or a child in their family, calculate when the child will be as old as they are. Next, find out what science predicts the world will look like in that year, look that child in the eye, and reflect on what may be in store for them. It also means education about all the five tenets of the ‘climate haiku’: not only what we are sure about and how bad this is, but also that we can fix it, and how.

Within education, particular attention must be paid to one field: Earth Science (a.k.a. the geosciences). Due to various developments in the history of the geosciences,1,33 basic knowledge about how the earth functions, its history, its timescales, and our influence on its future are lacking.

The Purpose of Interdisciplinary Philosophy

Interdisciplinary science communication and education, for their part, must be supported by interdisciplinary philosophy. Interdisciplinary philosophy literally means philosophy between disciplines. For philosophy, being in-between – or as Mieke Bal calls it, inter-ship 34 – first of all means that philosophy alone is not enough. Two recently deceased philosophers are examples of how this can be done in practice. Bruno Latour engaged with various topics beyond philosophy, such as our transforming relationship with the planet we live on. In Facing Gaia, he writes that it is as if “the décor had gotten up on stage to share the drama with the actors.”35 Bernard Stiegler, often described as a philosopher of technology but whom Daniel Ross argues should be understood as a philosopher of memory35, engaged in Technics and Time 37 with archeology, anthropology, and other disciplines that philosophers sometimes regard as too mundane.

If philosophy has to do with the creation and critiquing of concepts,38 then interdisciplinary philosophy also means recognizing when disciplinary scholars and scientists who might not identify as philosophers themselves are engaging in philosophical work. Marcia Bjornerud’s concept of timefulness is unearthed through the study of geology and the history of our planet. But it also builds on the Greek distinction between Chronos and Kairos to suggest how we might think about our relationship to the history that ‘we’ (homo sapiens) did not live, in a way that might secure a future in which we can live.39 Timefulness, rather than mindfulness, might be what philosophy is called upon to promote in our time on earth. Mieke Bal’s creation of travelling concepts is another move that might support this endeavor: concepts travel “between disciplines, between individual scholars, between historical periods and between geographically dispersed academic communities.”40 Interdisciplinary philosophy, rather than just philosophy, refers to using philosophy as a way to move between scientific disciplines and academic departments (Science, Social Science, The Humanities) and examine which concepts are helpful to work with. But it can also expand into moving between the disciplines of what I have termed “Earthucation”: philosophy, spirituality, science, politics, art, technology, and nature.41 For instance, science in the form of biology, physics, and the geosciences is not the only epistemic and ontological system we can use to understand nature. We can also benefit from the knowledge of spiritual and philosophical traditions that have been warning us about the climate crisis long before western science caught up.

What is the purpose of interdisciplinary philosophy? The purpose of philosophy, according to Berlin, is to address questions for which the shape of their answer is unknown in advance and there is no self-evident method for arriving at their answer(s).25 But philosophical questions are not necessarily questions that have no clear answer. On the contrary, often their problem is that they have too many answers, and they are too clear. In such cases, the

“task of philosophy, often a difficult and painful one, is to extricate and bring to light the hidden categories and models in terms of which human beings think – that is, their use of words, images, and other symbols – to reveal what is obscure or contradictory in them. Philosophy helps us discern the conflicts between them that prevent the construction of more adequate ways of organizing, describing, and explaining experience, for all description and explanation involves some model in terms of which the describing and explaining is done. At a still ‘higher’ level, the role of philosophy is to examine the nature of this activity itself (epistemology, philosophical logic, linguistic analysis) and bring to light the concealed models that operate in this second-order philosophical activity itself.”25

The climate crisis has arisen as a natural consequence of a certain way of thinking, acting, and being in the world – that is, a type of consciousness. There are many different possible names for this consciousness: technical rationality, capitalism, exploitation mindset, and so on. The crux is that this consciousness does not just determine which actions – such as extracting fossils from of the earth and treating them as ‘fuels’ – we select out of an a priori range of possible actions, but rather which actions occur as possible in the first place: “There are social contexts and conventions within which certain acts not only become possible, but become conceivable as acts at all.”42 This consciousness determines what makes sense in the first place and even what we can imagine. Our perception of ourselves and the world, what we consider real and illusory, is narrowly focused on action. Ironically, the type of consciousness that is narrowly focused on action is ineffective because it ignores the wider context from which this action arises.

Ultimately, therefore, the task of interdisciplinary philosophy is to expand our perception and intuition of our time on earth, of our planet, and our presence on it. As Henri Bergson writes,“Distinct perception is merely cut, for the purposes of practical existence, out of a wider canvas. […] Would not the role of philosophy under such circumstances be to lead us to a completer perception of reality by means of a certain displacement of our attention? It would be a question of turning this attention aside from the part of the universe which interests us from a practical viewpoint and turning it back toward what serves us no practical purpose. This conversion of the attention would be philosophy itself.”43

Understanding is not just a theoretical matter, but has the potential to expand our perception and imagination. It can transform the way our world occurs to us and which actions make sense. It might even motivate us to take the actions that we need to take to secure a future for our children.

References

- Bjornerud, Marcia. (2018) “III. Environmental Crises in Earth’s History: Causes and Consequences”. Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World, Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 190-192. https://doi.org/10.23943/9780691184531-012

- Bjornerud, M. (2022) Geopedia: A Brief Compendium of Geologic Curiosities. Princeton University Press, pp.12-13.

- Nicholas, K. (2021) Under The Sky We Make: How to Be Human in a Warming World. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, p.4

- Rutte will urge world leaders to “action, action, action” at climate summit, 1 November 2021 https://nltimes.nl/2021/11/01/rutte-will-urge-world-leaders-action-action-action-climate-summit

- “Statement On International Public Support For The Clean Energy Transition” November 4, 2021 https://ukcop26.org/statement-on-international-public-support-for-the-clean-energy-transition/

- IPCC Special Report “Global Warming of 1.5C”, October 2018 https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/

- “The Netherlands breaks major climate promise to end public financing for international fossil fuel projects” November 3, 2022 https://priceofoil.org/2022/11/03/the-netherlands-breaks-major-climate-promise-to-end-public-financing-for-international-fossil-fuel-projects/

- Van Gestel, M. (2022). “Nederland zou jaarlijks minstens 17,5 miljard aan fossiele subsidies betalen. Klopt dat?” Trouw, 9 december 2022. https://www.trouw.nl/a-b5398859

- https://sustentio.com/2022/climateinactionstripes-virale-klimakommunikation

- Latour B. (2017). Facing Gaia: Eight lectures on the new climatic regime: John Wiley & Sons. p.9, emphasis in original.

- Harvey, F. (2022). “Current emissions pledges will lead to catastrophic climate breakdown, says UN” The Guardian, October 26, 2022 https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/oct/26/current-emissions-pledges-will-lead-to-catastrophic-climate-breakdown-says-un

- World Health Organization (2021) “Climate change – the biggest health threat facing humanity” October 30, 2021 https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/climate-change-and-health

- Oreskes, N., & Conway, E. M. (2011). Merchants of doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

- Supran, G., Rahmstorf, S., & Oreskes, N. (2023). Assessing ExxonMobil’s global warming projections. Science, 379(6628), eabk0063. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.abk0063

- Speth, J. G. (2022). They knew: The US federal government’s fifty-year role in causing the climate crisis. MIT Press.

- McIntyre, L. (2021). How to talk to a science denier: conversations with flat earthers, climate deniers, and others who defy reason. MIT Press.

- Fisher, Mark. Capitalist realism: Is there no alternative?. John Hunt Publishing, 2009.

- Lamb, W., Mattioli, G., Levi, S., Roberts, J., Capstick, S., Creutzig, F., . . . Steinberger, J. (2020). Discourses of climate delay. Global Sustainability, 3, E17. https://doi.org/10.1017/sus.2020.13

- Wise J. Climate crisis: Over 200 health journals urge world leaders to tackle “catastrophic harm” BMJ 2021; 374 :n2177 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2177

- Romanello, M., Di Napoli, C., Drummond, P., Green, C., Kennard, H., Lampard, P., … & Costello, A. (2022). The 2022 report of the Lancet Countdown on health and climate change: health at the mercy of fossil fuels. The Lancet, 400(10363), 1619-1654. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01540-9

- Steenmeijer, M. A., Pieters, L. I., Warmenhoven, N., Huiberts, E. H. W., Stoelinga, M., Zijp, M. C., … & Waaijers-van der Loop, S. L. (2022). The impact of Dutch healthcare on the environment. Environmental footprint method, and examples for a health-promoting healthcare environment. https://doi.org/10.21945/rivm-2022-0127

- Karliner, J., Slotterback, S., Boyd, R., Ashby, B., Steele, K., & Wang, J. (2020). Health care’s climate footprint: the health sector contribution and opportunities for action. European Journal of Public Health, 30(Supplement_5), ckaa165-843. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa165.843

- McKibben, B. (2016) “When scientists protest, their picket signs have footnotes.” https://twitter.com/billmckibben/status/808791393569243140

- Thunberg, G. (2022). The climate book. p. 2

- Nielsen, K.S., Nicholas, K.A., Creutzig, F. et al. The role of high-socioeconomic-status people in locking in or rapidly reducing energy-driven greenhouse gas emissions. Nat Energy 6, 1011–1016 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41560-021-00900-y

- Berlin, I. (1996) “The Purpose of Philosophy.” Concepts and Categories: Philosophical Essays, edited by Henry Hardy, REV-Revised, 2, Princeton University Press, pp. 1–14.

- van Wijck, F., Dobrowolski, L. & Claessen, S. De huisarts heeft een belangrijke rol in de klimaatcrisis. Huisarts Wet 65, 46–48 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12445-022-1591-y

- Veen, M. Life From Plato’s Cave: A journey through reality and illusion. Manuscript in preparation.

- Jackler RK, Ayoub NF. “‘Addressed to You Not as a Smoker… but as a Doctor’: Doctor-Targeted Cigarette Advertisements in JAMA: Doctor-Targeted Tobacco Advertisements.” Addiction. 2018: 113: 1345–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.14151

- Little, B. (2019) “When Cigarette Companies Used Doctors to Push Smoking” History https://www.history.com/news/cigarette-ads-doctors-smoking-endorsement

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, Glober G, Beale EA, Kudelka AP. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-11. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302

- https://www.kimnicholas.com/climate-change-curriculum.html

- Bjornerud, M. (2008). Reading the rocks: The autobiography of the earth. Basic Books.

- Bal, M. (2013). Imaging Madness: Inter-ships. InPrint, 2(1), 51-70. [5]. http://arrow.dit.ie/inp/vol2/iss1/5

- Latour B. (2017) Facing Gaia: Eight lectures on the new climatic regime: John Wiley & Sons, p.3

- Life From Plato’s Cave (2022) “Episode 15 – Bernard Stiegler’s Philosophy with Daniel Ross” https://open.spotify.com/episode/7cD9GizC1Lg4HMgHxdrugZ?si=1775b978ed4f448e

- Stiegler, B. (1998). Technics and time: The fault of Epimetheus (Vol. 1). Stanford University Press.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1994). What is philosophy? Columbia University Press.

- Bjornerud, M. (2018). Timefulness: how thinking like a geologist can help save the world. Princeton University Press.

- Bal, M. (2009). Working with concepts. European Journal of English Studies, 13(1), 13-23. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825570802708121

- Veen, M. Earthucation: Our Time On Earth. Manuscript in preparation.

- Butler, J. (2020). Performative acts and gender constitution: An essay in phenomenology and feminist theory. In Feminist theory reader (pp. 353-361). Routledge. p.525

- Bergson, H. (1934) “The Perception of Change”, in The Creative Mind. Read Books. pp.167/16